By

Hayley Soh

BSc Anthropology with a Year Abroad

As a child, I grew up during the explosion of Britain’s ‘soft power’: One Direction was the most popular boy band with their throngs of screaming tween fans, Harry Potter and Sherlock were taking fandom by storm, and the “teaboo” trend was at its peak. If you’re unfamiliar with the word “teaboo”, it was a social media trend back in the 2010s where people loved British culture so much they wanted to emulate it, similar to the Japanese weeaboo (weeb) and the Korean koreaboo. Part of this aesthetic included twee fashion, mumsy Keep Calm and Carry On World War II posters, and of course, the much-imitated British accent.

The ‘British accent’ in question is the posh upper-crust received-pronunciation (RP) speech. Commonly referred to as the ‘Queen’s English’, it is accorded with the highest level of prestige due to its association with the then-most ceremonial and historically powerful person in the country. Because of that, there was always a sharp distinction drawn between this ‘posh and desirable’ accent and my own. Of course, I’m now more aware of the many different accents across the United Kingdom, the diverse histories they hold, and the different identities they represent. For example, the Cockney accent has its roots in the urban working class, and was frequently used in media to present stereotypes of people who had lower social status (Ranzato, 2018).

Singlish Perceptions in Singapore

Even back in Singapore, the way you speak matters. In a country that has experienced massive amounts of economic development over a short period of time (we gained independence in 1965), English language skills were emphasised very heavily in the workforce and education in order to allow Singapore to be taken seriously and compete on the international stage. As a former British colony, only the educated elite, who then went on to be the founding politicians, were afforded an English education (Wee, 2025). Most children were educated along racial lines, since philanthropy was carried out by organisations supporting their own ethnic1 group, such as Tao Nan School and Nan Chiau School founded by the Hokkien 会馆 (Clan Association) (Hue, 2024). These schools largely focused on a bilingual approach to education, meaning English language skills were not as strongly emphasised as they are in modern Singapore.

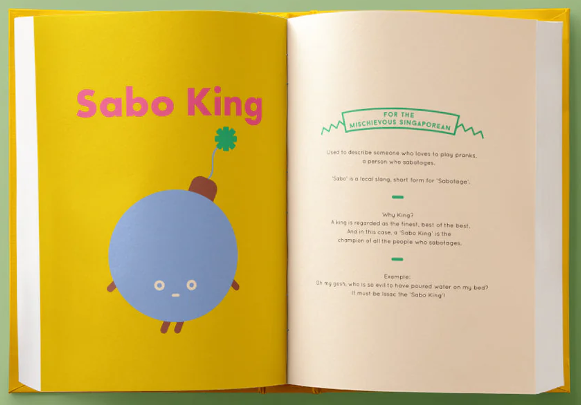

As a child, I was teased in kindergarten by my peers because I didn’t speak an ounce of Singlish, the local dialect. That same day, I tried to tag on a “lah”2 to my speech, which just resulted in my mother laughing at me for how unnatural it sounded. In casual settings like school, speaking Singlish was necessary to fit in and to be identified as part of a social group. Speech is an essential form of social interaction, and the way we speak contributes significantly to the way people perceive us.

In contrast, when going for scholarship interviews or conducting meetings with overseas clients, speaking Singlish is strongly discouraged and even looked down upon. In a professional setting, speaking in this ‘universal dialect’3 even with your peers is discouraged. This connects the very way we speak to something unsuited for a higher level of work, hence associating the dialect with a lower social strata. Similar to how the Scouse and Cockney accents are connected with the working class persona, the Singlish dialect automatically identifies the speaker with the ‘uneducated’ persona due to Singapore’s focus on English language abilities and the idealisation of Western professionalism.

Speaking Singlish in London

These shifting goalposts on how Singlish was policed in Singapore impacted the way I choose to present myself linguistically as an international student in London. Before moving abroad, I had heard stories from seniors on how they choose to code switch when speaking to their British friends or interact with service staff for a variety of reasons: to be understood better, to fit in, or even out of shame. From the other end of the spectrum, I was nagged at by my aunties and friends back home to not return home with a British accent because they didn’t want to see me betray my roots. Coming to London with both perspectives in mind, I decided to let fate take its course and just see whether the way I speak would change naturally.

Two months in and nothing has changed despite efforts from my British friends to introduce a British accent. I’m not sure how to feel about it. On the one hand, I’m happy that the way I speak is still faithful to my heritage, and that I haven’t compromised my identity to assimilate into the ‘local culture’. On the other hand, I do feel the bone-deep sense of otherness and isolation, exacerbated by colonial baggage. This specific form of internalised racism as a result of Britain’s colonial legacy in Singapore makes me feel like the way I speak is uncouth and unrefined, especially in comparison to the sharp consonants and distinct intonations of RP. Cultural differences, like not understanding references to the local geography, or feeling horrified when your friends step into your room without taking off their shoes, can be masked or ignored. But having your difference reflected back at you through speech is something I cannot escape.

I’ve attempted to hide my Singlish using the excuse of not wanting to confuse my non-Singaporean friends, but I recently gave up the act after finally admitting to myself the real reason I was doing this: the fear of being judged for the way I sound. I realised this was a form of self-discrimination – self-censoring because I anticipated the prejudice, bias and intolerance I’d face. I took the steps to prevent them before even attempting to be myself (Mehta and Buckley, 2022). This ‘bleaching’ of my racial identity for the Western palate was not entirely necessary, purely because no one was making me chip away at or dilute my identity: the pressure was completely internalised.

My story reveals how Western linguistic standards are still expected and enforced globally as a result of colonisation. Linguistic insecurity reproduces old hierarchies that place Eurocentric ideals at the peak of the pyramid. And while it’s difficult to shake these entrenched and subconscious beliefs, I encourage everyone to challenge these norms. As anthropology students, we should be able to embrace local dialects as a marker of pride instead of deficiency, and to learn about cultures through linguistic multiplicity.

References

Adhikari, B., Amaratunga, C., Mukumbang, F.C. and Mishra, S.R. (2025). Why should we be concerned by internalised racism in global health? BMJ Global Health, [online] 10(6), p.e016740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016740.

Bo, M. (2023). MANAGING CHINA- SINGAPORE RELATIONS AMID US-CHINA RIVALRY. [online] Available at: https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/TRS19_23.pdf.

Hue, G.T. (2024). Contributions to education by Hokkien community in Singapore – Culturepaedia: One-Stop Repository on Singapore Chinese Culture. [online] Culturepaedia: One-Stop Repository on Singapore Chinese Culture. Available at: https://culturepaedia.singaporeccc.org.sg/communities/contributions-to-education-by-hokkien-community-in-singapore/ [Accessed 23 Nov. 2025].

MFA, (2025). Foreign Policy. [online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Overseas-Mission/Bangkok/About-Singapore/Foreign-Policy [Accessed 23 Nov. 2025].

Mehta, P. and Buckley, C.D. (2022). ‘Your people have always been servants’: internalised racism in academic medicine. The Lancet, [online] 400(10368), pp.2045–2046. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02486-2.

Ranzato, I. (2018) ‘The Cockney persona: the London accent in characterisation and translation’, Perspectives, 27(2), pp. 235–251. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2018.1532442.

Wee, T.B. (2025). An Overview of Singapore’s Education System from 1819 to the 1970s. [online] Available at: https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-5/issue2/jul-2009/singapore-education-system-overview/ [Accessed 23 Nov. 2025].

Photos from: @pk_kenzie on Twitter/ X, @giraffeoverlord on Pinterest and Strangely Singaporean book via Cat Socrates