By Kelly Barrett • BSc Anthropology

Landing into Montego Bay Airport is a sight that is truly unimaginable. Greeted with tropical waters and vast green land, you surrender to the beauty without having stepped on the Island yet. Due to the high amount of biodiversity, the local Jamaicans have learnt how to utilise the land and live harmoniously with other organisms. Multiple stories and oral histories transferred to me from my mother and father demonstrate the relationships that the locals have with the Island, some of which I will incorporate below (if you’re feeling really brave, try to read everything my dad says in Jamaican Patois).

Burning the Rush

Mom: Why don’t you speak to your dad about when he used to burn the rush?

Me: What do you mean burn the rush?

Mom: When we lived in Jamaica your dad and grandad used to go to the land out at the back and set all of the grass on fire, I don’t know why, you’ll have to ask him.

When my mother first spoke to me about ‘burning the rush’, we were having a discussion about farming practices in Jamaica. As my family (and many others who live in Jamaica) used to practice farming as a way of life to support the family and provide a secure means of income, I always find myself getting into discussions with my parents about previous agricultural practices. I found that ‘the rush’ was a term used for the grassland which covered an area we used to own close to where we lived. After speaking to my dad about why they used to burn the rush, I discovered that there was some uncertainty as to why that practice was carried out. My dad just went along with what my grandad was doing and therefore was unable to provide me with much information. Nevertheless, it was interesting to hear about how this act of burning the rush did not destroy the land, but rather acted as a means for food security. After the rush was burnt, the space would then repair itself.

Me: Do you remember why you used to burn the rush with grandad in Jamaica?

Dad: I used to go with him. I don’t know why we did it but we would burn all the grass and it would catch a fire all the way down to the bottom of the land and then when it all burn down, there would be plenty of crab holes and we used to catch the crabs and eat them, then the grass would grow back and we would do it again. We used to keep doing it, the grass would never die, it would always grow back.

From the explanation my father gives, we can see how burning the rush is a cyclical agricultural process, a process which allows for the exposure of crab holes and therefore the creation of a recurring food source. As they take control of the spread of the fire and are knowledgeable of when they can reburn the rush once it grows back, we can see how the environment is both utilised and maintained with minimal destruction.

Go Drink Tea

Anytime I fall ill, both of my parents always tell me to “Go drink tea”. By ‘tea’ they aren’t talking about Tetley’s. In Jamaican culture it’s not common to run to the doctors straight away as many natively found and grown plants in Jamaica are known to have healing properties. These are often used to make herbal teas. As American Anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston wrote in Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica, “the island has more usable plants for medicinal and edible purposes than any other spot on earth” (page 3).

I support this statement as when I was growing up, I swear some teas could cure me in a day or two. For example, I remember that a brew of Cerasee tea from the Cerasee plant (Momordica Charantia), known to detoxify and purge the body, helped me recover extremely quickly from common colds and stomach aches.

These plants are also used in medicinal baths and as ‘body creams’ to be applied to wounds, burns and skin conditions. Whilst we don’t live in Jamaica anymore, my parents still grow an Aloe vera (Aloe sp.) plant at our home in Sheffield to “tie on to wounds and pull out infections”. As I get older and carry on my family traditions, I gain a better understanding of the relationships that people build with plants, and other organisms on the earth.

Doctor Birds

The Jamaica national bird is the swallow-tailed hummingbird, also known as the Doctor Bird. I always thought it was given this name due to its long bill, used to extract nectar from flowers, which resembles a doctor’s needle. However, the meaning behind the name is ambiguous. In Jamaican folklore, the bird not only acts as an emblem to the island but is also an object of superstition. The native inhabitants of Jamaica, the Arawak Indians, first called the bird the ‘God Bird’ due to the belief that they were the reincarnation of an ancestor who would walk with them. The bird still seems to carry spiritual significance.

Dad: You can’t kill a Doctor Bird. If you hurt one or kill one, you will go to prison. They live on the island with us.

My father demonstrates the interrelatedness between Doctor Birds and Jamaicans. Found only on Jamaican territory, the Doctor Bird is an expression of Jamaican culture but equally holds underlying sacred meanings. As Jamaican’s have this connection with the doctor birds, they are protecting them and ensuring their survival, illustrating how human-animal relationships could act as a wider sector in wildlife conservation attempts. My father regularly speaks to me about the doctor birds and how much they mean to Jamaican people and through oral histories and Caribbean folklore, other young Jamaicans continue to appreciate their importance.

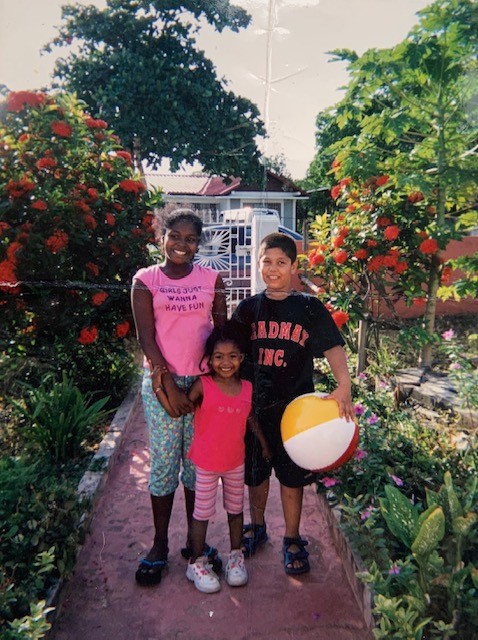

I had my first encounter with a Doctor Bird as a small child whilst I was sat in the grass of my grandparents’ garden. In front of me was an abundance of flowers of all different colours and then suddenly a sharp flicker caught my attention. An iridescent bird, expeditious and elegant, came to pollinate the flowers and although I was frightened by its unanticipated appearance, I was left fascinated by its beauty. Of course I tried to touch it, but gave up after many failed attempts. Later on in life at a funeral, a family member told me she had videos of me when I was younger trying to catch the butterflies in Jamaica. I think it’s safe to say that catching birds and insects isn’t at the top of my skillset. However, reminiscing on these early experiences with nature has led me to realise that the environment and the animals and insects which inhabit it have always been a prominent aspect to my life. Furthermore, my journeys back to Jamaica and conversations with family members have given me a wider understanding as to why people-plant-animal relationships are so significant within Jamaican culture.

Through oral histories and Caribbean folklore, my parents continue to educate me on the importance of being knowledgeable about the environment. There is still a lack of research into traditional ecological knowledge held by local peoples of Jamaica and their level of expertise in terms of their natural surroundings. I mean, this sounds like an idea for a dissertation project?

References

Hurston, Zora Neale. 2009 [1938]. Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. New York: Harper Collins.